Tutorials | Guitarmaking Tips | Web Sites

By Tod Riggio

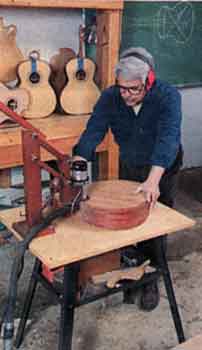

But is there a need for more guitar makers? "Oddly enough," Schmukler says, "there seems to be. Doing this is a lot like being a musician. You go to a conservatory, you learn your chops and then you go out and become a master musician by playing and playing and playing. Building guitars is very much the same. We teach you the basics and get you much further along than anyone I know of.." The school's approach There are courses for both beginners and advanced students at Leeds, housed in a 600 sq. ft. shop in an arts, college town. One luxury of working in a guitar shop– except for the person who writes the checks to the utility company–is a 70 degree temperature year-round, in order to keep the humidity at about 40 percent. Since guitars are made from very thin pieces of wood, constant humidity levels of 40-45 percent are necessary so the wood won't swell with moisture in the summer or dry out in the winter. Beginners are welcome in the two-week basic construction courses, where students make a guitar from pre-dimensioned sets of wood and rough-shaped parts. Thee courses cover the entire process of assembly, fretting, binding, final shaping, stringing and setup. Students cut the guitar's sound hole, bend the wood bindings and join the back, but shortcuts .have to be taken. "There are a couple places where serious mistakes can be made, so we try to avoid those in the basic classes," he said. "The most important joint in the entire guitar is the top plates–its two bookmatched pieces of wood on the long seam. We want students to learn how to do that, but we don't want them practicing on a top which is expensive, and we like to get right into things. "When I'm building a guitar, I have a drawer full of parts. So the students do, too." There are 13-week extended-intensive courses scheduled for the late summer and fall, which cover tool crafting, parts fabrication, basic flat-top guitar construction, basic arched-top guitar construction, finishing and repair. For the experienced builders, the curriculum now includes instruction on contemporary basic The school also offers one-day work shops on spray finishing and French polishing, and a longer finishing course that includes repair techniques. Intense stuff According to Schmukler, students work like crazy until about 4 p.m. and then one of the teachers will deliver a lecture. There is no power-tool work after 2 p.m. And before the sun sets, Schmukler heads for his favorite stream to unwind. "This is very intense work," he said. "The attention to detail is something a lot of people aren't used to. That's a different skill than, say, cabinetmaking because of the amount of handwork involved. There's a different method of sharpening and a different way of using your tools." In the long course, students learn how an edge tool works, then about power tools. The students have use of the school's table saw, band saw, sander and jointer to make the parts, though 90 percent of the work is done by hand. But when people come here, they walk out with a guitar." The goal of the school is to keep the technology low so students don't have to spend a fortune to build guitars. Students are taught to make many of the tools. Schmukler figures it takes about $1000 to obtain all the tools necessary to make guitars, and he's not against purchasing finished parts, like fret boards. The school also devotes time to the woods used to make guitars and how they are processed. "We teach about bracing stock and where it's really critical to have properly quartersawn wood. That's-the top and the braces; neck, second; backs and sides, third," Schmukler said. "A guitar will hold up best, of course, with quartersawn wood all the way around because it is a structural whole." The staff Class size is Limited to four to six students, and there is usually no more than a 3-to-l student/teacher ratio. In addition to Schmukler, the staff features Brad Nickerson, Alan Chapman, Ed Diehl and Steve Warshaw. Schmukler described the teaching credo as instructing the students to make guitars simply, with the least possible expenditure of energy and above all to make them work. "The teachers here are recognized professionals," Schmukler said;' We 're catering to [students] who can go into business building between 10 and about 200 guitars per year. The level of technology that we bring into this is mostly for one- or two-person operations. "We're also strictly hands on. There's a certain amount of demonstrations, the tools. Schmukler figures it takes about $1,000 to obtain all the tools necessary to make guitars, and he's not against purchasing finished parts, like fret boards.

However, some methods are required. "The only thing I'm really dogmatic about is dovetailing. I think a handmade guitar should have dovetailed necks," he said. The other option is a bolt-on neck, more common in manufactured guitars. But nuts and bolts tend to loosen over time, which creates unwanted vibration. Most of the instruction is acoustical. "We haven't really taught much by way of solid body, electric instruments, " Schmukler said. "We do carved-top electrics, which are acoustic-electrics and acoustic carved-tops–the regular jazz guitars." The school also teaches dovetail neck resetting and refretting , both of which are common repairs. Schmukler estimates that 90 percent of steel-string guitars have dovetail necks, and since the guitar is considered to be a "failing" structure because the top eventually distorts under the load of the strings, the neck has to be realigned every five to 25 years. Demographics The school averages about 20 students per year, all of whom must be tightly focused on-their goals — the class schedule is six days a week and eight hours a day. "Guitar making is the first thing they think of when they wake up, and the last thing they think of when they go to sleep," Schmukler said. Students have ranged in age from 14 to 75, while the median is 30. It's not unusual for a student to have no previous woodworking experience. "We're seeing younger people now," Schmukler said. "At the point where there was the whole downsizing thing years ago, there were a lot of older people who were looking for something to do in retirement. We still see that." Something Schmukler finds very encouraging and long overdue is that more women are taking the courses. In fact, he predicts that more than half this year's students will be women. "I think the craft really suffers for lack of female input," he said. "Most guitar players are men. ~ think it' about 25 percent women, 75 percent men, and for the most part the business is dominated by men." A brief interlude Schmukler started repairing guitars -in1965 and was building guitars by 1972. His dad was a jeweler and a sculptor, so a home woodshop was always available. He grew up about 30 miles from the C. F. Martin & Co. plant in Nazareth, Pa., makers of Martin Guitars, and used to hang around there as a kid. Although he stopped making guitars for about 13 years, he's been back at it for much of the last decade. Schmukler said there were about a half-dozen guitar makers when he started. When he came back, there were two associations for guitar makers, several publications and every place you turned "there was another bloody guitar maker." This year, classes were booking up almost two months earlier than- usual and were almost half filled. "We don't give a certificate of luthier," Schmukler said. "At the end of the classical guitar-building course, we have a bottle of champagne. At the end of the steel-string building course we have a bottle of beer. "We're a craft school; not a vocational school. We don't promise people jobs, but we do refer." But that may change "Our goal is to put together a three-year program, similar to the program at the MittenwaId School in Bavaria, where they make violins," Schmukler said. "The first thing students do is cut down the tree. Students also have to learn how to play at least- to the point that they can properly register an instrument in terms of its action geometry and intonation. We would grant a certificate for that," he said. "I think if you're going to grant a certificate, it needs to be for a full curriculum of study. We'd be teaching dendrology, construction, a little bit of engineering, musical theory, acoustic theory and nontraditional as well as traditional guitar making." Contact: Leeds Guitarmakers, 8 Easthampton Road, Northampton, MA 01060. Tel: 413-582-0034. E-mail: info@leedsguitar.com. Web site: www.leedsguitar.com.

|

Building a "worId-cIass academy of fretted instrument technology" can consume most of Ivon Schmukler’s days. Over the past five years, about 70 students have come to the Leeds Guitarmakers’ School for hands-on instruction in design and construction of steelstring, flat-top, arch-top and classical guitars. And in a few years, the staff is working to expand the school’s offerings to fill a three-year program.

Building a "worId-cIass academy of fretted instrument technology" can consume most of Ivon Schmukler’s days. Over the past five years, about 70 students have come to the Leeds Guitarmakers’ School for hands-on instruction in design and construction of steelstring, flat-top, arch-top and classical guitars. And in a few years, the staff is working to expand the school’s offerings to fill a three-year program. patterns, the use of synthetics in bracing, lattice bracing systems, and other 20th- and 21st-century methods of bracing for classical guitars.

patterns, the use of synthetics in bracing, lattice bracing systems, and other 20th- and 21st-century methods of bracing for classical guitars. "We really try not to be dogmatic about the stuff we teach," Schmukler said. "All the people who teach here have slightly different methods of accomplishing the same ends. We make sure there is always someone working over your shoulder, but there are different methods of doing all these things that we like to expose them to. We encourage the student to do it in the way that's most comfortable."

"We really try not to be dogmatic about the stuff we teach," Schmukler said. "All the people who teach here have slightly different methods of accomplishing the same ends. We make sure there is always someone working over your shoulder, but there are different methods of doing all these things that we like to expose them to. We encourage the student to do it in the way that's most comfortable."

"I was never more than 100 yards from a really well-equipped woodshop," he said. "Some of the tools here are from that shop. I was processing wood about the same time I started fly-fishing."

"I was never more than 100 yards from a really well-equipped woodshop," he said. "Some of the tools here are from that shop. I was processing wood about the same time I started fly-fishing."